- Biblical Maps

- Home Page

- History of Israel Blog

- Ancient Mesopotamia

- Map of Palestine

- Abraham

- Ancient Israel

- 12 Tribes of Israel

- Jerusalem

- The Book of Isaiah

- Palestine

- The Habiru

- Contact Us

- Bible Study Forums

- Media Page

- Visitors Sitemap

- Privacy Policy

- The History of the Old Testament

- In the Days of Noah

- The City of Jericho

VISIT OUR FACEBOOK PAGE!

The Akkadians & the Habiru

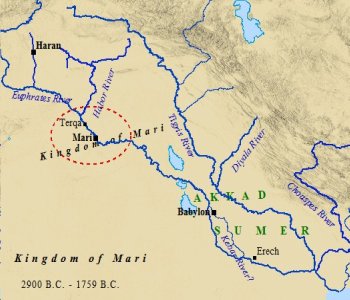

Akkadians & The Kingdom of Mari

Akkadians made up the kingdom of Mari, whose northern branch later came to be known as the Assyrians.

North of the Taurus Mountains, in modern day southern Turkey, lie the ruins of ancient Kultepe. Kultepe is approximately 800 miles north of Sumer, once a great city of the Akkadian Empire.

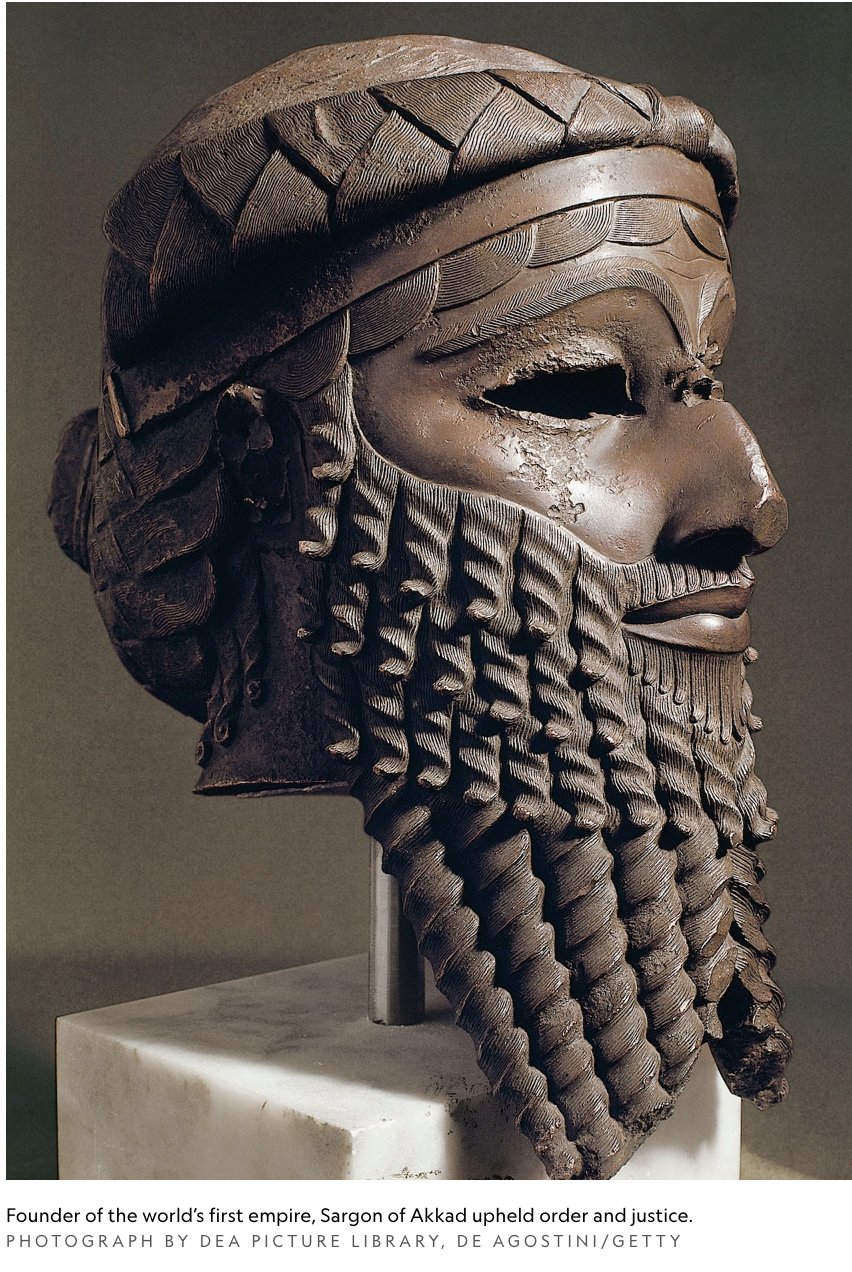

The Akkadians established their empire in Mesopotamia from the years 2350 B.C. - 2000 B.C. The land of southern Mesopotamia was known as the land of Sumer and Akkad during this period.

Excavations in Kultepe, and north of Kultepe in Alishar, have unearthed Assyrian trading stations dating from the Old Akkadian Period, dating from 2500 - 1900 B.C.E - including the reign of Sargon the Great.

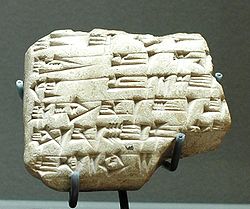

Documents were recovered from these stations describing a group of Akkadians that had imprisoned a group of men referred to as Haberi. It is significant to note that the logogram SA.GAZ was not used in this instance. In the Akkadian language, "SA.GAZ" and "Haberi" become synonymous with each other. In this letter, an Assyrian merchant is beseeching the Akkadians for the release of "Haberi men" in their custody.

"Concerning the Haberi men in the palace of Shalahshuwe who are present in custody, I sent word to you thus: 'Consult there with the princes and the chamberlains as to whether they will return them or will not return them. Then send word to me. If they will not return them, redeem those men. Whatever the ransom for them the palace asks of you, let me know in your message that I may send it to you. Let your hand seize those men. Whatever response the palace makes to you concerning those men, let me know in your message. The men have much ransom money.' "

It is apparent this merchant thought highly of the Haberi men in custody. He begs their release throughout the letter and even mentions he will send money for their release if necessary.

It is also noteworthy these Haberi are well off financially. They possessed enough money of their own to pay the ransom for their release. These Habiru certainly appear in a much different light than those in ancient Sumeria - often depicted as a fringe-like social element wandering in herds outside of cities. However, many similarities do exist between the two groups in Sumer and Turkey.

One such example is the seemingly constant attention these people draw from the legal authorities. As is the case in many of the Sumerian references, these Haberi in Turkey find themselves in a legal conundrum with the local Akkadians. Though the exact date of these documents is unknown, it proves that various groups of individuals identified using the logogram SA.GAZ, or Haberi, were located in southern Anatolia (Turkey) around the same time other Habiru were dwelling around southern Mesopotamia.

These separate groups of SA.GAZ/Haberi were hundreds of miles apart, and operated completely independent of each other. By 2000 B.C.E., if not considerably before, these people were widespread and already an established part of different societies in different kingdoms.

SHARE YOUR COMMENTS ON THE HABIRU. Do you have special insight into the Akkadians? Do you have insight into the Habiru? What are your opinions and thoughts? Give us your insight, questions, comments, and thoughts by clicking on the link above!

Study Resources

The Epic of Gilgamesh is one of the oldest compositions in

recorded history. It tells the story of the ancient Mesopotamian flood

story, remarkably similar to the Biblical flood in Genesis. Many

scholars feel Enkidu was, in fact, Enoch of the Bible! This edition is

the original version, based on the original Akkadian, Babylonian and

Sumerian tablets. Click on the link below to re-direct to Amazon.com and

The Epic of Gilgamesh.

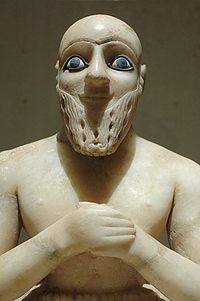

AKKADIANS

The Mari Tablets (1800 - 1750 B.C.E.)

The city of Mari is located on the western banks of the Euphrates River approximately 250 miles north of Babylon. Archaeology has shown the city flourished from 2900 B.C.E. to 1759 B.C.E., at which point it was sacked by Hammurabi. Mari was a part of the Amorite kingdom which dominated Mesopotamia in the 18th century BCE.

The Akkadians established this empire stretching from Babylon, northeast to Asshur, northwest to Haran, and across to the Mediterranean. Abraham is believed to have existed during the reign of this Amorite kingdom.

His journey from Ur to Haran more than likely carried him through the city of Mari. The Akkadians in Mari kept impeccable records of their kingdom. These records, once discovered in the modern era, would lead historians to rewrite the historical time line of the Ancient Near East.

In the 1930's over 25,000 Akkadian tablets were discovered in the archives of Mari. These tablets provided invaluable information on the kingdom of Mari, its customs, culture, religion, and even names of people. These tablets date to the last fifty years of Mari's independence, 1800 - 1750 B.C.E.

The Mari tablets revolutionized the view of the ancient world by shedding light on over 500 names of different places. Important discoveries were also made on the identity of the SA.GAZ/Haberi/Habiru, and their interactions with the Akkadians of this time. One Cappadocian tablet stands out in particular.

In this tablet the verb "Habiru" appears. It has been translated by Birot as "imigrer" - related to immigrant. Other scholars, such as Bottero, disagree with this definition. Bottero claims it should translate as "refugee". Though the Cappadocian tablet is the earliest occurrence of the word "Habiru", dating to the 19th century B.C.E., it should be noted that both scholars may be correct in their assessment.

The Akkadians were constantly at war between individual city-states. Within the documents regarding these disputes the SA.GAZ/Haberi appear in numerous accounts. One account speaks of a certain man named Yapah Adad. He had built up the city of Zallul, located on the banks of the Euphrates. He stationed himself in Zallul, along with 2,000 "Habiri" soldiers. It is not presumptuous to assume these 2,000 soldiers had hired themselves out to Yapah Adad as mercenaries. In this instance Habiri may refer to the mercenary-nature of these soldiers.

In yet another tablet, a chief by the name of Izinabu is said to have had 30 "Habiru" men march in his charge. One tablet, though much of it damaged and indecipherable, speaks of "300 asses of the Haberi". It is intriguing special attention is paid to the donkeys belonging to the Haberi. Throughout the Old Testament, donkeys are mentioned as an important part of ancient Hebrew life.

Another tablet speaks of the skill "Habiru" soldiers displayed during a night raid. Under the cloak of darkness these men raided the town of Yahmuman. They attempted to seize other towns, apparently unsuccessfully, yet did raid Luhaya confiscating 500 sheep and 10 men.

One immediately notices the rather liberal terms used to designate these bands of people. In one instance they may be immigrants, perhaps refugees fleeing Akkadian war, maybe mercenaries. Perhaps the overall tone is that of a displaced social element, or a social element made of malcontents. From the Sumerians, and later adopted by the Akkadians, comes the cuneiform designation SA.GAZ.

The Akkadians pronounced this word "Habiru". Yet, other similar terms are used as well; Habiri and Haberi. One insightful tablet speaks of the young Prince Idrimi. This tablet becomes especially significant when evaluating the Habiru/Hebrew connection. The tablet reads as follows:

"My horse, my chariot, and my groom I took and departed. The wasteland I crossed and into the midst of the Sutu warriors I entered. With them I spent the night in my covered chariot. The next day I moved along and went to the land of Canaan. In the land of Canaan the town of Ammiya is located. In Ammiya dwelt people of Halab, Mukish, Ni and Amau. When they saw that I was the son of their former lord they gathered about me and said: 'It has been much for you, but it will cease.' Then I dwelt for seven years among the SA.GAZ warrior. I interpreted (the flight of) birds; I inspected (the intestines and livers of) lambs; and thus seven years of Adad/Teshup turned over my head."

This is a remarkably illuminating piece of information regarding the Habiru. In summary, a young prince by the name of Idrimi left his clan of Habiru, destination unknown. After spending a certain amount of time in his new home, he experienced some sort of trouble and was exiled. He decided to spend his exile in his homeland, located somewhere in the land of Canaan.

Idrimi then set out for the land of Canaan. Upon arriving, the residents discovered he was the son of their former leader. He was thus welcomed back and allowed to live peacefully among the Habiru warriors. He studied the ways of nature, looking for prophetic signs his exile was over and it was safe to return to his homeland. He was, in essence, the prophet of his tribe.

This depicts the Habiru as migratory, moving from one land to another, and portrays the way in which many of these bands may have been formed. Idrimi asks for asylum, and is given such being allowed to dwell within the Habiru camp.

To this point the Habiru have been seen as a negative element in society, constantly at strife with the law and other kingdoms. They come from all levels of society, from all corners of the Near East and are employed at various occupations and levels of government. They tend to excel in matters of war, as many become mercenaries. The picture painted, thus far, is one of a rebellious and defiant people.

However, Nadav Na'aman argues the Akkadians view of the Habiru in the Mari tablets have changed the perception of the Habiru. He points to three tablets in particular to stress his point.

ARM 14 50

The text of this tablet speaks of a man named Ami-ibal. He was a native of the town of Nasher, in Ilansura. Ami-ibal had migrated, the verb used is Habaru, to Subartu.

The tablet accuses Ami-ibal of being registered as an elite soldier in his native Ilansura, and he is thus accused of defecting. The term used as defector is "Pateru".

Ami-ibal rejects this accusation on the grounds he migrated (Habaru) to Subartu four years prior to the alleged registration. His reasons for leaving are not given, and he had just recently returned to his homeland as a result of the advance of Atamrum.

Na'aman points out there is a clear distinction between a "Pateru", and a "Habaru". Desertion (Pateru) was a major offense. Governments sought the extradition of deserters from other countries, and in some cases punished them by death. However, migrating (Habaru) was not considered an offense at all, but rather a legal, and voluntary act.

ARM 14 72

The Akkadians in Mari were said to have accepted a certain Babylonian overseer named Addu-sharrum. An overseer was one who led a group of soldiers. Addu-sharrum, along with his band of warriors, served Mari as replacements in the military.

According to the story on the tablet, eight months passed, at which point the Babylonian government demanded his extradition.

The Babylonians claimed Addu-sharrum and his warriors deserted from their stations as the army passed through Mari. He and his men had defected, and according to law, must be extradited back to Babylon to face punishment.

Addu-sharrum claims he and his men fled from Babylon to Mari, thus they were migrants, or refugees. As Habiru, they were not subject to extradition.

The governor of Saggaratum, Yaqqim-Addu, was the author of this letter. He sends Addu-sharrum to the king of Mari. In this letter he beseeches the king to see if Addu-sharrum "fled from Babylon or whether he came up with the troops and then stayed."

ARM 14 73

This letter is connected to ARM 14 72. However, only the second half of the letter has survived. The men of Addu-sharrum are quoted by Yiqqim-Addu as saying:

"Is there a country which extradites its replacements? Not only us: a messenger who was used to hearing the secrets of his lord, if he enters the service of another king, he becomes the son of (that) country. Now, why should you extradite us?"

These letters speak to the difficulty in defining the legal status of the Habiru. The Akkadians, thus, were not alone in their difficulty in interpreting the status of the Habiru in their kingdom.

However, it is significant that the common thread of each letter deals with people who had left their homeland and migrated to another land. The core of the question lies in the difference between Pateru and Habiru. In these letters, Habiru is not a negative element. In fact, quite the opposite is stated.

The Habiru are legal immigrants, seeking the protection of their new governments. They are distinguished from the criminal behavior of a Pateru. They fled their homelands under persecution, for whatever reasons, thus fitting the description of what constitutes a refugee.

Once again, a remarkable Hebrew/Habiru connection can be made to David in the Old Testament book of I and II Samuel. David, fleeing persecution from Saul, seeks the protection of King Achish of Gath, the rival Philistine king. He even fights with the Philistines against the Israelites. The Philistines welcomed David, for the most part, rather than sending him to Saul to face death.

Conclusion

Na'aman points out another class of people similar to, but quite distinct from, the Habiru. The term "Munnabtu" is used frequently to denote an assortment of runaways and outcasts. The term is even used to refer to runaway slaves.

In many instances, the Mari tablets treat the Munnabtu and Pateru in the same manner. They are individuals accused of a crime, and thus subject to punishment.

On the other hand, as was the case with the Akkadians in the Mari tablets, the Habiru were regarded as migrants. They were exempt from such treatment. Once these individuals were confirmed as Habiru, or legal migrants, they were permitted to dwell in whatever kingdom they had fled to.

Throughout ancient Near East kingdoms Habiru were given asylum, free from extradition or prosecution. Bottero's interpretation as "refugee" thus seems in harmony with the above references. Sumerian and Akkadian perceptions of the Habiru were as outlaws, or aliens, sometimes as resident aliens. The Akkadians obviously did not view all Habiru with contempt, simply as foreigners.

Na'aman argues these designations were used to describe the Habiru after they had migrated, as they settled into their new homelands.

However, in the Mari tablets it seems evident that it is soley the act of migration which distinguishes one as a Habiru. The Mari tablets illuminated the diversity of the Habiru people. They come from diverse regions, spread across the Near East.

They served at all levels of society, from Princes, to soldiers, to shepherds. Even in the military their roles were diverse. Some were foot soldiers, others were charioteers.

They were distinguished from runaways and outcasts. They were protected legally by their new kingdoms. They oftentimes received payment in the form of livestock and sheep. Some of the Habiru interacting with the Akkadians possessed large sums of money.

The Mari tablets perhaps demonstrate most accurately the original perception of the Habiru people. They emerge from the perspective of the Akkadians as people on the move.

Migrating from their homelands, joined together with other immigrants, or refugees, they seek out employment in their new societies.

They take on a variety of occupations, in order to reintegrate themselves into some form of established society. They also have a strong connection to animals; particularly, sheep, asses, and other livestock.

The Habiru, in these regards, do not appear as a threat to society, as they had in previous documents from other cultures.

Back to the Akkadians

Back to the Habiru

Back to Home Page

SAMUEL the SEER

Now Available in Print & eBook on Amazon!!

POPULAR TOPICS

Learn more about these popular topics below. The Bible is full of fascinating stories, characters and mysteries!

BIBLE MAPS

Explore the land of the Old Testament! View these maps of the Bible.